Universal Freemasonry

TO THE GLORY OF GOD

The Mystery: Why Does It Matter?

“Why

do you care whether there is a God, or extraterrestrials,

reincarnation, or any of that? What relevance does it have to your

life?”

This

is a question which I have often heard, in one form or another, when

bringing up topics related to the mysteries of life, from those who are

not typically inclined to ponder them. Personally, I have always found

the mysteries irresistible, so this common refrain has always been

somewhat baffling to me. How could you really not care

whether there is a God, or extra-terrestrial life? Such apathy toward

the ultimate questions of life seems unfathomable, to me.

Indeed,

those who find themselves involved in Freemasonry are generally those

who are inclined to explore these questions, and this is part of what

draws us to the craft, esotericism in general, and what is often

referred to literally as The Mysteries.

This is also why the fellowship of a brotherhood of truth seekers is so

precious to those who find it, because our kind so often feel alone in a

world full of those who care more about their bank balance, newest

electronic gadget, or mundane interpersonal dramas than the quest for

ultimate reality.

So,

like a fish trying to describe the ocean, for a long time it was

difficult for me to articulate why these things matter to me so much

when this question arose. However, I eventually did manage to create

some semblance of an explanation, which I would like to share with you

now. Perhaps by reading this, you will have a new answer in your

repertoire the next time someone asks why you seek truth.

The

short version is: I care about the mystery because the mystery is the

ultimate context of my existence, and context is absolutely everything;

the context of a thing defines that thing and gives it meaning. Allow me

to explicate.

The Universal Existential Constant

The

human condition is defined by a finite or limited conscious existence,

and a mystery beyond it. In fact, I believe that this is probably the

condition of not just humans, but any entity, since any finite

consciousness is always limited, by definition. If it had no limits, it

would not be an “entity,” it would be infinite.

The

human condition is defined by a finite or limited conscious existence,

and a mystery beyond it. In fact, I believe that this is probably the

condition of not just humans, but any entity, since any finite

consciousness is always limited, by definition. If it had no limits, it

would not be an “entity,” it would be infinite.

In

other words, there are things you directly experience, and there are

things beyond that, with a gradient boundary between them. Regardless of

how far your awareness may expand, there is, a priori, always a boundary to it and always something beyond that boundary, which to you is a mystery.

The

only possible exception to this would be if our awareness became

infinite, perhaps, but we cannot really imagine that. Barring the

hypothetical exception of infinity, there is always a boundary to

conscious existence, and therefore, a mystery beyond it.

This

would presumably also be true for any self-aware finite entity, from

the lowliest worm to the most vast super-intelligent species, or even

advanced spiritual beings. If they are not infinite, then it seems to me

that their existence must have this structure: the known, the unknown,

and the boundary between.

The Existential Island in an Ocean of Mind

One

helpful metaphor is to think of our existence as a sphere, like a

planet. That planet has its basic substance or ground, which for us is

our direct sensory awareness. These are the things we are most certain

of, because we directly experience them, and in this metaphor, they are

our ground or earth, which also relates to our colloquial sayings about

being “grounded” in reality. This is the reality to which we refer, our

most certain, sensory reality, the bedrock of our experience.

One

helpful metaphor is to think of our existence as a sphere, like a

planet. That planet has its basic substance or ground, which for us is

our direct sensory awareness. These are the things we are most certain

of, because we directly experience them, and in this metaphor, they are

our ground or earth, which also relates to our colloquial sayings about

being “grounded” in reality. This is the reality to which we refer, our

most certain, sensory reality, the bedrock of our experience.

Then,

there is another layer which is beyond the ground of sensory

experience, but which is near enough to be relatively certain; you can

liken this to the atmosphere of our metaphorical “planet” of existence.

For us, these would be facts outside of our senses, but nevertheless

trustworthy, thanks to evidence and logic (to put it briefly).

For

instance, I can be relatively certain that oxygen exists, a faraway

country like Russia is really there, and that I have a liver, even

though I’ve never truly seen or experienced any of those things. Thus,

there are things I have not directly experienced, yet of which I am

relatively certain. Here is where the boundary begins.

Finally,

beyond that of which we are relatively certain, there is the larger

Mystery, about which we ponder, and upon which we weave the fabric of

our beliefs, by combining reason with imagination. To continue our

planet metaphor, this would be the vast starry expanse in which our

planet is suspended. Just as the cosmos is the context of a planet,

whatever is beyond the boundaries of the ground and atmosphere of our

existence forms the context of it.

Thus,

the mystery is the context of our existence, and is experienced purely

in the realm of imagination, hopefully tempered by reason. Regardless of

what is actually “out there” beyond what we know with varying degrees

of certainty, our experiential existence floats in a cosmos of mind and

imagination because we can only imagine and reason about what is beyond

the boundary of our experience and certainty.

Not

only that, but no matter how far we expand our knowledge and

experience, it always will float in an ocean of imagination and mystery,

because that seems to be the inherent structure of any finite,

experiential entity. How else could it be?

Context is Everything

So,

“Fine,” you might say, “the mystery is the context; why should the

context matter to me?” My answer to this is that the meaning of anything

essentially is derived from its context. Let’s take a very concrete

example: a bar fight.

So,

“Fine,” you might say, “the mystery is the context; why should the

context matter to me?” My answer to this is that the meaning of anything

essentially is derived from its context. Let’s take a very concrete

example: a bar fight.

Let’s

say that you witness a fight break out between two men in a bar. If you

know absolutely nothing about the context of this fight, it will mean

very little to you; perhaps you may have some thoughts about the

volatility of alcohol and testosterone when combined in too great a

quantity. In other words, to you, it is a relatively meaningless

occurrence.

Let’s

say that you now expand your knowledge, when someone tells you that the

reason they fought is that one man was sleeping with the other’s wife.

Now, to you, this is a very different bar fight, is it not? Yet, it is

the same bar fight; it is the context of it in your own mind and

imagination that has changed. Let’s say that you hear from yet another

person that the reason the affair occurred in the first place is that

the husband was abusing her; yet again, another vastly different bar

fight.

Let’s

say, hypothetically, that your spiritual “third eye” suddenly opened,

and you were able to see that this was an unfolding of karmic patterns

through time that had been in motion for thousands of years between

these two souls, as they weave a pattern of flesh-bound experiences in

and out of various bodies and lifetimes, trying to find a balance and

transcend the illusory nature of this physical reality, for their

ultimate mutual enlightenment. Yet again, a totally new bar fight, with a

totally different meaning.

Why?

Because with every expansion of your knowledge of the context of the

fight, your experience of the fight transforms. The same is true of your

entire experiential existence, the same principle is in operation every

time you learn, and explore the mysteries.

That,

my friends, is my answer to the question of why the mystery matters. To

me, this is like something I had always subtly known but for the

longest time had difficulty articulating. Perhaps it may strike you the

same way, as almost obvious, yet novel in it’s explanation; or, perhaps

you somehow disagree, in which case I would love to hear your

perspective.

Either way, I hope that you have enjoyed it. Thanks for reading!

The Sacred Tetractys: Why do Freemasons connect the dots?

If

Pythagoras found himself transported to the modern world, he would have

much to learn about technology, science, and human thought. But is there

something Pythagoras can still teach us today in his symbol of the

tetractys? What do the dots reveal? How is it significant to

Freemasonry?

To start

with, tetractys refers to a symbol of the Pythagoreans which consists of

four rows of dots containing one, two, three, and four dots

respectively which form an equilateral triangle. Many have found the

tetractys full of sublime meaning.

When did the

tetractys first come about? To answer this question may be more

difficult. Very little is known about the real Pythagoras, or rather too

much is “known” about him, but most of it is surely mistaken. The

biographical trail is scattered with contradictions. It combines the

sublime, the absurd, the inconceivable, and the just plain weird.

The

teachings are elusive because he never wrote anything down. His

treatises are only known to us through other Greek researchers.

Consequently, it is up to present-day scholars (and there are many) to

sift through these works in order to find a common thread that can be

genuinely ascribed to Pythagoras.

We do know

that Pythagoras was born in Samos in the sixth century B.C.E. Pythagoras

was both a mystic and a scientist, although some scholars tend to

praise his mathematical prowess while looking away with embarrassment at

his perceived “mysticism.” For Pythagoreans, they were one and the

same.

The Science of Number

was the cornerstone of the Pythagoreans. It describes, if not yet

everything, at least something very important about physical reality,

namely the sizes and shapes of the objects that inhabit it.

The Pythagoreans influenced the world by the simple expression:

“All is number.” – Pythagoras

What Did Pythagoras mean by this famous motto “All is Number?”

Is it

possible to listen to this message today afresh, with Pythagorean ears?

What teaching does the tetractys offer a Freemason?

The Tetractys: A Masonic Lecture by William Preston (1772)

Freemasons

in earlier times thought highly of Pythagorean philosophy. Brother

Manly Palmer Hall, a 33° Mason dedicated an entire chapter in his work “The Secret Teachings of all Ages” to the both mystical and philosophical qualities of Pythagorean numbers.

Freemasons

in earlier times thought highly of Pythagorean philosophy. Brother

Manly Palmer Hall, a 33° Mason dedicated an entire chapter in his work “The Secret Teachings of all Ages” to the both mystical and philosophical qualities of Pythagorean numbers.

Hall wrote:

“The ten dots, or Tetractys of Pythagoras, was a symbol of the greatest importance, for to the discerning mind it revealed the mystery of universal nature.”

Hall states that if one examines the tetractys symbolically a wealth of otherwise hidden wisdom begins to reveal itself.

The

Prestonian Lectures (1772) give us further insight into some of the

possible masonic thinking on the tetractys in the 1800’s. It was the

subject in one of the series of lectures written by Brother William

Preston for instruction and education of the Lodge members.

An excerpt of the Lecture (1772) goes as follows:

“The Pythagorean philosophers and their ancestors considered a Tetractys or No. 4:

- 1st as containing the decad;

- 2nd as completing an entire and perfect triangle;

- 3rd as comprising the 4 great principles of arithmetic and geometry;

- 4th as representing in its several points the 4 elements of Air, Fire, Water and Earth, and collectively the whole system of the universe;

- Lastly as separately typifying the 4 external principles of existence, generation, emanation, creation and preservation, thence collectively denoting the Great Architect of the Universe Wherefore to swear by the Tetractys was their most sacred and inviolate oath.”

In other

words, it is taught to Freemasons that a four-fold pattern permeates the

natural world, examples of which are the point, line, surface and solid

and the four elements earth, water, air and fire. Musically they

represent the perfect consonants: the unison, the octave, the fifth and

the fourth.

The Divine Creator in Freemasonry is sometimes referred to as The Great “Architect” or Grand “Geometrician”

always building the universe through the creative tools of the

geometer. Tetractys itself can be interpreted as a divine blueprint of

creation.

Some say

that Pythagoras and his successors had two ways of teaching, one for the

profane, and one for the initiated. The first was clear and unveiled,

the second was symbolic and enigmatic. In order to achieve mastery of

this universe, a person has to discover the veiled meaning of numbers

hidden in all things.

I have often wondered if we could hypothetically peer into the mind of the Grand Geometrician, and the veil was lifted, what design would we see?

The Grand Design

Perhaps we would see how the Master Builder

has ordered all things by measure and number and weight. Throughout the

structure of the universe the properties of number are manifested.

Geometry is fundamental to the work of the masonic builders. It is

engaged with the first configurations of the Plan upon which the form is

erected and the idea materialized.

Examining numbers symbolically, they represent more than quantities; they also have qualities. Brother H. P. Blavatsky in the “Secret Doctrine”

tells us the numbers are entities. They are mysterious. They are

essential to all forms. They are to be found in the realm of essential

consciousness. They are clues to our evolution.

Blavatsky

emphasizes that the study of numbers is not only a way of understanding

nature, but it is also a means of turning the mind away from the

physical world which Pythagoras held to be transitory and unreal,

leading to the contemplation of the “real.”

Personally, I

find that the masonic teachings in all their many symbolic forms a good

way to study numbers. The reason I continually come back to Pythagorean

philosophy is the tradition of music theory. In music, the Divine

patterns of the Grand Geometrician are expressed in musical

ratios. Harmony through sound, therefore, can be applied to all

phenomena of nature, even going so far as to demonstrate the harmonic

relationship of the planets, constellations, elements and everything,

really. The reason being that all life vibrates, like the string.

Why do

Freemasons connect the dots? Like many symbols, the tetractys can lead a

craftsman down a rabbit hole of self-discovery. By rabbit hole, I mean a

portal into a mysterious and infinite wonderland of formulas filled

with beauty, confusion and intrigue – a place to encounter all sorts of

adventures with concepts beyond our wildest dreams that keeps us coming

back for more.

“The more deeply we study the processes of nature the greater in every direction becomes our admiration for the wonderful work of Him who made it all.”

– C.W. Leadbeader

Note: The full Prestonian Lecture on the Tetractys and Masonic Geometry can be referenced in Ars Quatuor Coronatorum, Volume 83.

Service: Why Do We Help?

If

you were to ask five different people of five different belief systems

why it’s important to serve others, you’d probably get five somewhat

different answers. For instance, a Hindu might say that it will accrue

positive karma, a Christian that it’s to spread the love of Christ, and

perhaps a scientific atheist might say that it simply reduces the amount

of suffering in the world, and that is reason enough.

The

teaching that we should serve others is almost universal in the various

religions and wisdom teachings of mankind, although their stated

reasons may vary, as one might expect. To most of us, it seems obvious

that it is good to serve others, to help those in need. But as

Freemasons, what is our explanation? Why do we help?

Freemasonry

defines itself as an organization based on service to humanity, and

masons throughout history have spoken on the subject of service to

humanity extensively, and focused heavily on both charity and

enlightenment. As with every other philosophy or belief system, our

perspective on service is deeply rooted in the masonic perspective on

humanity’s essential nature, and destiny.

An

important caveat is necessary, here: technically, there is no single

“masonic perspective,” because each mason chooses for him or herself how

they think about any given topic. Freemasonry is a fellowship among

truth-seekers, not an orthodox belief system. Therefore, the ideas

presented here are in no sense meant to be understood as universally

accepted by all masons.

The Vector of Human Evolution

In

Freemasonry, and the Western esoteric traditions in general, we do

generally have a particular perspective on humanity’s purpose. We do not

typically view it in the way that some religions might, which is often

the idea that humanity was created merely to worship and please a deity,

nor do we generally believe that humanity’s existence is randomly

purposeless, a chance occurrence in an otherwise dead and meaningless

universe, as might those skeptics who believe only what science can

prove.

In

Freemasonry, and the Western esoteric traditions in general, we do

generally have a particular perspective on humanity’s purpose. We do not

typically view it in the way that some religions might, which is often

the idea that humanity was created merely to worship and please a deity,

nor do we generally believe that humanity’s existence is randomly

purposeless, a chance occurrence in an otherwise dead and meaningless

universe, as might those skeptics who believe only what science can

prove.

One of the most deeply-held core values of freemasonry is that humanity does in fact have a teleological vector,

which is a fancy philosophical way of saying that we believe humanity

has a purpose, a trajectory, an inherent potential which each and all of

us are in the process of unfolding. We may have differing ideas about

what that purpose entails, or what its ultimate goal is, but the common

thread is that we believe a process is taking place which involves a

perfecting or evolution of each person, so that we eventually become

something more and better than what we were before, both individually

and collectively.

In

fact, it is this vector which underlies the current and overall purpose

of Freemasonry. This is one understanding of what we term The Great Work, the progression towards the highest potential in the self, and in humanity as a whole.

Service in Context

So, what does all of this have to do with service, you might ask?

If

we believe that all people have this higher potential which is yet to

be unfolded, then our chief task in this world must be to unfurl it in

our self, as well as to do whatever possible to help the people we come

into contact with to do the same. In other words, to catalyze and cultivate the process of human evolution towards our destiny. That is my attempt to encapsulate the essence of service, from the perspective of the esoteric wisdom teachings.

If

we believe that all people have this higher potential which is yet to

be unfolded, then our chief task in this world must be to unfurl it in

our self, as well as to do whatever possible to help the people we come

into contact with to do the same. In other words, to catalyze and cultivate the process of human evolution towards our destiny. That is my attempt to encapsulate the essence of service, from the perspective of the esoteric wisdom teachings.

When

most people think of service and charity, they probably wouldn’t think

about contributing to our evolutionary process. We might simply think

it’s the “right thing to do,” or that our compassion simply compels us

to do so. People are suffering, so we do what we can to provide relief;

many people are lacking in knowledge, so we do what we can to provide

insight and enlightenment. If we are able, we help those who are not

able. For many, it feels almost written into our DNA. Why do we need an

explanation?

These

reasons are good enough, insomuch as they spur us to action. However,

in my opinion, the best possible understanding of the purpose of service

must necessarily be embedded in, and in alignment with the purpose of

our entire existence. To me, there is value in seeing things in the

larger context of what we ultimately believe about ourselves, our

species, and the universe itself.

Climbing the Pyramid

Any

of us who are blessed enough to have found some measure of spiritual

awakening in this life find ourselves in a peculiar situation, in

respect to our relationship with the rest of humanity.

It

is a fact of life, and has been for as long as there have been those

who wake up to some degree, that the majority of humans exist in a state

of confusion and suffering. This suffering is not purely economic,

although poverty is a real problem. Those who have their basic needs

taken care of, or even those who live in lavish luxury, can and do still

suffer a great deal on an emotional, social, and soul level. And this

is precisely the state which we ourselves seek to extricate ourselves

from.

Yet,

we know from the understandings handed down to us from various wisdom

teachings that each of those confused and suffering people contains a

divine spark, and the potential to ignite that spark, and transmute

their suffering, thereby transforming into a vibrant, soulful, and

purposeful human being. Whether we know it or not, I believe that this

is the ultimate purpose of service, not simply to reduce suffering to

reach some state of equilibrium, but to free up resources to realize a

higher potential in each person.

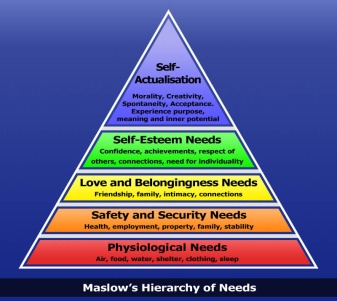

Many readers will be familiar with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs,

perhaps from Psychology 101. For those who aren’t familiar, it is a

model of human needs which arranges them in a pyramidal structure,

grouped into levels, each needing to be satisfied before the next level

can be advanced. At the base are the most basic, biological needs, and

they transition up the pyramid into emotional and social needs, with the

capstone being self-realization, the fulfillment of some transcendent

purpose that is beyond all the others below it. The key idea is that one

must take care of the needs in sequence, from bottom to top. If the

basic needs are not addressed, the higher needs will remain unfulfilled.

Many readers will be familiar with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs,

perhaps from Psychology 101. For those who aren’t familiar, it is a

model of human needs which arranges them in a pyramidal structure,

grouped into levels, each needing to be satisfied before the next level

can be advanced. At the base are the most basic, biological needs, and

they transition up the pyramid into emotional and social needs, with the

capstone being self-realization, the fulfillment of some transcendent

purpose that is beyond all the others below it. The key idea is that one

must take care of the needs in sequence, from bottom to top. If the

basic needs are not addressed, the higher needs will remain unfulfilled.

So,

if the capstone of that pyramid is equivalent to the destiny towards

which we are moving, and which we hope to assist all of humanity in

achieving, then helping those around us means helping them move beyond

the level where they currently exist. For those whose basic needs still

are unsatisfied, we would not necessarily hand the deepest teachings of

soul wisdom. It may simply be that they need food to eat or a roof over

their head. For yet others, mental/emotional stability may be their

current requirement. Yet, in all of these, the reason we help is the

movement towards that capstone of ultimate good, even transcendence.

In

this way, if we wish to be good servants to our Creator and our

fellows, it’s helpful to first be able to recognize which service is

required, depending on where that person is at, and how we are best

equipped to provide it. This begins with a concrete conceptual model of

the hierarchy of needs, as well as the ultimate goal.

Tending the Garden

I

find the garden to be a useful metaphor both in inner work, as well as

work with other people. To me, the relationship between those who wish

to serve a higher purpose and the rest of life and humanity is similar

to the relationship of a gardener to a garden. In this vein, we are not

the sole rescuers or providers of the essential life processes. Rather,

we should best view ourselves as Life’s humble and equanimous

attendants.

I

find the garden to be a useful metaphor both in inner work, as well as

work with other people. To me, the relationship between those who wish

to serve a higher purpose and the rest of life and humanity is similar

to the relationship of a gardener to a garden. In this vein, we are not

the sole rescuers or providers of the essential life processes. Rather,

we should best view ourselves as Life’s humble and equanimous

attendants.

We

cannot make the garden grow, the flowers blossom, or the vegetables

ripen, but we can water them, prune them, prop them up when they have

fallen, and dig out the weeds. If more of us are wise, conscientious,

and faithful stewards, then the garden of human civilization will be

more sweet with the scent of compassion, bright with the colors of

inspired expression, and fulfilling with the fruits of human

self-actualization.

The Freemason’s Words: Can the Secrets be Googled?

In a

discussion with a few masonic friends recently, someone asked the

question: Why are oral traditions fading away? One could dispute the

premise. Still, I think the brother was onto something. Are oral

traditions still relevant? Are they slowly being replaced with

technology?

In its

plainest form, an oral tradition is information passed down through the

generations by word of mouth that is not written. Examples might be

legends, stories, proverbs, riddles and so on. Certain modes of

recognition, including masonic words and passwords are considered part

of the oral tradition in Freemasonry.

Where did

masonic customs originate? The tradition becomes more understandable if

we look back before the 1600’s. At that time, masonic lodges were

stonemasons’ guilds of builders whose “secrets” concerned how to

construct buildings. The hidden modes of recognition, whether they were certain passwords or handshakes, were a

way to identify an impostor passing himself off as the real thing. The

“operative” masons were artisans that were the best at their craft.

recognition, whether they were certain passwords or handshakes, were a

way to identify an impostor passing himself off as the real thing. The

“operative” masons were artisans that were the best at their craft.

recognition, whether they were certain passwords or handshakes, were a

way to identify an impostor passing himself off as the real thing. The

“operative” masons were artisans that were the best at their craft.

recognition, whether they were certain passwords or handshakes, were a

way to identify an impostor passing himself off as the real thing. The

“operative” masons were artisans that were the best at their craft.

For reasons

that are still not entirely clear, lodges evolved from “operative” to

“speculative” builders. The “speculative” masons were different in that

they became more interested in arcane studies. Their secrets were no

longer building trade secrets but based on moral and philosophical

concepts. When Masonry identified itself as a speculative craft, it

placed the meanings of its allegories and symbols within a realm that is

more esoteric.

Some say

that these more esoteric secrets were inspired from ancient traditions –

such as Rosicrucianism, Gnosticism, or Hermeticism – however the

theory is hotly debated. An opposite view is that the passwords in

freemasonry are not meaningful at all. They are not particularly

earth-shattering, nor are they exactly secret. I have heard many times

recently – “just google them.”

This current debate begs the question. When it comes to a mason’s words, are they a meaningless carry-over from former times? Or to the contrary, do they have some  deeper significance for masons today?

deeper significance for masons today?

deeper significance for masons today?

deeper significance for masons today?

Definitions by Albert G. Mackey

Usually when

I have a question or questions that I have been wondering about, I must

confess I use any resource available, including the internet to

research that topic and related topics. At the same time, I am very

careful. There are many things that I will read “everyone knows” that

are simply untrue. It is amazing how many things fit this category.

Often when confronted with some sort of puzzle in masonic research I go to Mackey’s Encyclopedia of Freemasonry. In this case, he lays out some very interesting distinctions between the various kinds of masonic words.

Mackey gives several different definitions –

- Recognition Word: Identifies one brother to another as a means of recognition.

- Lost Word: Relates to the mythical history of a venerated lost word in which a temporary word was substituted.

- Sacred Word: Applies to the unique word of each degree, to indicate its peculiarly sacred character.

- Significant Word: Used as a word that is equivalent to a sign in each degree of the craft.

- True Word: Indicates a symbol of Divine Truth.

As you can easily see, he illustrates a hierarchy of words. Some words, like recognition words, are more matter of fact, the ones that can be transmitted mouth to ear. But other words, like the True Word are more mysterious. The True Word, he says, is the most philosophic and sublime.

The Word becomes the symbol of Divine Truth, the loss of which and the search for it constitute the whole system of Speculative Freemasonry. ~ Bro. Albert Mackey

Is it

possible, then, that the real secrets of Masonry cannot be heard by the

ear or uttered in words? If this is true, where are the secrets hidden?

When faced

with deep philosophical questions it’s sometimes nice to look at

old allegories for wisdom. Here’s one of my favorites.

Man’s Divinity: Where to Hide the Stolen Jewel?

There was a time in the history of the race when the gods stole from man his divinity, and meeting in a high conclave, sought to decide where to hide that which they had stolen.One god suggested that they hide it on another planet, for there man could not find it, but another god arose and said that man was innately a great traveler and they had no guarantee that, eventually, he might not find his way there.“Let us,” he said, “hide it in the depths of the sea, at the bottom of the ocean for there it will be safe.”But again, a dissenting voice was heart, and it was pointed out that man was great natural investigator, and that he might someday succeed in penetrating to the deepest depths, as well, as the greatest heights.

(As you

might suspect, the problematic discussion ends with one member of the

conclave suggesting as the final hiding place the following location…)

“Let us hide the stolen jewel of man’s divinity within himself, for there he will never look for it.”*

The Secrets of True Masonry

Sometimes

when we think of The Craft, we only think of meetings, dues, minutes,

and rituals, etc. True Masonry, however, is a system of enlightenment.

It is a quest for the hidden within us, the precious jewel. The Lodge is

a bastion of virtue. Add to this the desire to live the high principles

of Brotherly Love, Relief, and Truth. Then add the passion for

creativity to make the “builder’s art” truly artistic through the Arts

and Sciences.

BEHOLD! You have found the true secrets of Masonry.

Like all the things most worth knowing, no one can know it for another, and no one can  know

it alone. It is known only in fellowship – by the touch of life upon

life, hand to hand, breast to breast, spirit upon spirit.

know

it alone. It is known only in fellowship – by the touch of life upon

life, hand to hand, breast to breast, spirit upon spirit.

know

it alone. It is known only in fellowship – by the touch of life upon

life, hand to hand, breast to breast, spirit upon spirit.

know

it alone. It is known only in fellowship – by the touch of life upon

life, hand to hand, breast to breast, spirit upon spirit.

The secrets

are a way for Masons to bond with another. It’s something we all share

together. Each person knows “The Word” according to his own quest and

capacity.

Humanity has

always been filled with curiosity about things unknown or unseen. I

like to think that oral traditions have not disappeared. Their settings

may change, but their power and use remain.

Can the

secrets be Googled? Sure, you may find some interesting facts about the

Craft. In the end, however, the best hiding places for the mason’s

mysteries are where we least expect them.

The attentive ear receives the sound from the instructive tongue, and the mysteries of Freemasonry are safely lodged in the repository of faithful breasts. ~ Masonic Monitor

*Note: The ancient allegory can be referenced in Foster Bailey’s Spirit of Masonry.

Can You Make the Climb?

The Three Initiates, who authored the book The Kybalion, speak of seven Hermetic principles that guide the Universe. One of those principles is the Law of Polarity.

In brief, this law says that qualities such as love and hate, fear and

confusion, etc. are truly the same quality of life that differs only in

gradient.

The Kybalion uses a great exemplar when it mentions hot and cold. There is no scientific line drawing the thermometer in half saying, “any object who measures above this number is hot and any that falls below is cold.”

thermometer in half saying, “any object who measures above this number is hot and any that falls below is cold.”

thermometer in half saying, “any object who measures above this number is hot and any that falls below is cold.”

thermometer in half saying, “any object who measures above this number is hot and any that falls below is cold.”

There is no

more a line for hot and cold as there is for any pair of opposites. This

may be a strange thing, but try it for yourself. Take a particular vice

and locate its virtue. Now try to see if you can find a concrete

division between the two. When does the vice become a virtue? When does the virtue move into its vice? Finding

the changing point is much harder than realized. It is much akin to

trying draw a physical line on the ground for when you first clear the

fog. Near impossible.

Now ask

yourself what the “opposite” of Science is, and my bet is you will say

Religion. Most do. Why? Because it seems that Religion is the other pole

to a fundamental principle pendulum. These two are a particular

expression of the greater idea of Knowledge.

Let’s us apply the Law of Polarity to Religion and Science. Imagine yourself on a small  silver

ball that is tied to a string and that string is swinging towards one

pole, then the other, and then back again. Continually moving in this

way. There is sort of an exhilaration to it, yes? Swinging back and

forth hearing the cacophony of arguments rushing in our ears. The

adrenaline of this rhythmic movement plays the background music of the

constant Science-Religion debate, enticing us to stay; however, it is

time we stand up to temptation.

silver

ball that is tied to a string and that string is swinging towards one

pole, then the other, and then back again. Continually moving in this

way. There is sort of an exhilaration to it, yes? Swinging back and

forth hearing the cacophony of arguments rushing in our ears. The

adrenaline of this rhythmic movement plays the background music of the

constant Science-Religion debate, enticing us to stay; however, it is

time we stand up to temptation.

silver

ball that is tied to a string and that string is swinging towards one

pole, then the other, and then back again. Continually moving in this

way. There is sort of an exhilaration to it, yes? Swinging back and

forth hearing the cacophony of arguments rushing in our ears. The

adrenaline of this rhythmic movement plays the background music of the

constant Science-Religion debate, enticing us to stay; however, it is

time we stand up to temptation.

silver

ball that is tied to a string and that string is swinging towards one

pole, then the other, and then back again. Continually moving in this

way. There is sort of an exhilaration to it, yes? Swinging back and

forth hearing the cacophony of arguments rushing in our ears. The

adrenaline of this rhythmic movement plays the background music of the

constant Science-Religion debate, enticing us to stay; however, it is

time we stand up to temptation.

There are

several problems that plague this never-ending battle between Science

and Religion. One of the problems (and there are many) is the great

misunderstanding of the purpose of Science. There are those on both

sides who claim that Science is in pursuit of Truth, but this is simply

not so. Unfortunately, the philosophy of science is not a common topic

at parties or dinner tables (or many science classrooms); so the masses

are mostly unaware of the purpose of Science. Don’t worry such

discussions didn’t exist at my dinner table either.

To be clear, Science is not

in the pursuit of Truth, and true Science, unadulterated Science. will

never be. The very foundational reasoning behind it precludes this

possibility. Rather, Science is in the pursuit of understanding.

It wants to understand how your genetic sequence works, the health

affects of that coffee you are drinking, and how to make the plastic you

use safer. Science is looking to improve its understanding with every

new discovery, and it is rightfully unapologetic in doing so. The late

Richard Feynman said Science can only tell you how a thing works, not why it works.

Truth

requires more than just knowing the how. It requires so much more. There

is a freedom to not being the custodian of Truth, and we should liberate our misconceptions of Science as that custodian.

of Science as that custodian.

of Science as that custodian.

of Science as that custodian.

The debate

between Science and Religion will most likely never end. The pendulum

will always swing; we cannot get off this particular ride. Hate won’t do

it; apathy especially won’t. But that doesn’t mean we have to engage in

the incivility that cloaks ignorance occurring on both sides.

Let us do what The Kybalion

speaks to. Climb up. Climb the string so that we are swayed less by

misquoted “facts” and down right mud-slinging. The climb isn’t

difficult.

Pick up a

book, read more than one article and from different points of view, but

most of all ask questions and speak less. Science has ever been the

observer, the person in the field looking up at the night sky asking why

– not hollering the question at his neighbor. Human beings seek. We

have all our existence, and what better place to best see the landscape

than at the highest point of the pendulum? At the top of the string.

The Sun as a Symbol in Freemasonry: What is it trying to tell us?

“There is nothing so indestructible as a symbol, but nothing is capable of so many interpretations.” – Count Goblet d’Alviella

What does a

symbol have to do with you or me? Well, it’s possible that it doesn’t

have anything to do with us. On the other hand, the meaning behind a

symbol just might be pretty significant. To know what a symbol means (or

at least what we think they means) is one of the important speculative

studies in Freemasonry. The teachings of the craft are said to be

“illustrated by symbols.”

What are

symbols? The definition of a symbol is something that represents

something else through resemblance or association. As the well-known

saying goes, a picture tells a thousand words! There are everyday

symbols and then there are the more universal and esoteric symbols which

we are mainly concerned with as Freemasons.

Esoteric

symbols are those with a hidden meaning. They have been used throughout

time in the great spiritual traditions to guide seekers after truth.

Esoteric symbols both conceal and reveal the truth.

For example,

I consider myself to be a seeker of truth. The other day, I chanced

upon the following passage about the esoteric symbol of the sun. It set

me thinking on a number of different levels:

“The blazing star, or glory in the center, refers us to the sun, which enlightens the earth with its refulgent rays, dispensing its blessings to mankind at large and giving light and life to all things here below.” – Masonic Lectures

What

are we to make of this statement? Why would the blazing star, usually

depicted as a five-pointed star, be a symbol of a sun, too? And if it

is, what is different about this sun?

What

are we to make of this statement? Why would the blazing star, usually

depicted as a five-pointed star, be a symbol of a sun, too? And if it

is, what is different about this sun?

While the

answers to these questions remain a mystery, some of us may know that

the blazing star makes its appearance in several of the masonic degrees,

and the pieces to the puzzle reveal more of the secrets at each stage.

How, then, do you study a symbol? How do you know if what you are interpreting is truth?

A Symbol: Exoteric, Conceptual, and Esoteric

I have found

with symbols, it’s possible to go overboard with analysis. Especially

as Freemasons, we love to “speculate.” We open the whole thing for

scrutiny and dissect every little piece to see where it leads. We use

lots of words while trying to nail things down: “This means this” and

“that means that.”

Unfortunately,

in my opinion, when we over-analyze, especially early on, we may

unintentionally rob the symbol of its power. In the end, we may have

analyzed it to death.

The good news.

The

process of symbolic analysis, while wrought with paradox, is actually

doing something beneficial to the mind. The best summary of this idea I

found in a theosophical article of the Beacon Magazine (1939) written by Alice Bailey. The article details how the mind is actually being trained when we study symbolism.

The

process of symbolic analysis, while wrought with paradox, is actually

doing something beneficial to the mind. The best summary of this idea I

found in a theosophical article of the Beacon Magazine (1939) written by Alice Bailey. The article details how the mind is actually being trained when we study symbolism.

Bailey gives three ways that a mind can analyze any symbol.

- Exoterically: This concerns the concrete or objective appearance, its form and structure.

- Conceptually: This concerns the concept or idea which the sign or symbol embodies.

- Esoterically: This concerns the energy or feeling that you register from the symbol.

Studying a

symbol in three ways, she says, is activating the mental mechanism on

all three levels: concrete mind (exoteric), higher mind or reasoning

(conceptual) and the intuitional mind (esoteric). The goal is to arrive

at a synthetic concept.

Why does the

process matter? Bailey says that practical work with symbols over time

serves to bring a student closer to truth. It lifts an individual out

of their emotions; it develops clarity of perception; it energizes the

mental life; it shifts the focus and attention and consciousness out of

the world of illusion into the world of ideas. How then could

Freemasons apply this technique?

Let’s take an example.

Freemasonry: The Point within a Circle

The sun is often symbolized by a symbol called the circumpunct. For those of you who’ve read the novel by Dan Brown called The Lost Symbol, you probably are familiar with what a circumpunct is. For those who aren’t familiar, it’s simply a point within a circle.

The sun is often symbolized by a symbol called the circumpunct. For those of you who’ve read the novel by Dan Brown called The Lost Symbol, you probably are familiar with what a circumpunct is. For those who aren’t familiar, it’s simply a point within a circle.

There are

hundreds of things the circumpunct can represent, anywhere from the “Eye

of God” to the “Google Chrome” icon that I use to launch my search

engine. Using the Bailey technique, the circumpunct could be studied

and reflected upon by an inquiring student and hopefully, after a little

while, reveal a synthetic understanding of what it means.

Freemasons for centuries have taken a stab at analyzing the circumpunct.

W.L. Wilmshurst, for example, says this:

“As the sun is the centre and life-giver of our solar system and controls and feeds with life the planets circling round it, so at the secret centre of individual human life exists a vital, immortal principle, the spirit and the spiritual will of man. This is the faculty, by using which (when we have found it) we can never err.”

In other

words, Wilmshurst (and many other masonic scholars) see the point within

a circle to be where we, as Freemasons, stand. It is the point from

which we cannot err. The point is timeless, eternal, subjective,

immeasurable, invisible, absolute. For these reasons, it is often

attributed to Deity and the Sun.

As

Freemasons, the study of symbols helps us to make sense of ourselves in

relation to the universe. Planetary symbols such as the sun, moon,

stars, and blazing stars inspire the contemplative mind to soar aloft and read the wisdom, strength and beauty of the Great Creator in the heavens. They challenge us to dig deeper on matters of eternal significance.

As

Freemasons, the study of symbols helps us to make sense of ourselves in

relation to the universe. Planetary symbols such as the sun, moon,

stars, and blazing stars inspire the contemplative mind to soar aloft and read the wisdom, strength and beauty of the Great Creator in the heavens. They challenge us to dig deeper on matters of eternal significance.

Sun or

blazing star? I’ve learned there seems to be a certain humility in

recognizing that we may never fully understand a symbol in a complete

way, one that allows us to cross it off the list and totally explain its

meaning.

How do you know if what you interpret in symbols is true? Perhaps the better question might be:

Where is it true?

If I may,

“Truth is within ourselves. It takes no rise

From outward things, whate’er you may believe.

There is an inmost centre in ourselves,

Where truth abides in fullness…

– Robert Browning

Note: The last image is an engraving by Alexander Slade dated 1754, titled “A Free Mason Form’d Out of the Material of his Lodge.” For further study, see the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library.

The Socratic Method: Does It Lead A Mason From Darkness To Light?

“I can’t teach anybody anything. I can only make them think.”

So says

Socrates, a great thinker of his time in Ancient Greece. He was known

for educating his disciples by asking questions and thereby drawing out

answers from them, called the Socratic method. The goal was to nudge

people to examine their own beliefs, instead of unthinkingly inheriting

opinions from others. The approach was a way for his students to find

the truth of anything. Thinkers have venerated the method ever since. It

really worked for the Greeks.

I have

always had a fascination with Greek culture. I particularly enjoy

studying Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. I also admit to getting lost in

Greek mythology at times, enjoying Greek food, and have always secretly

wished that I could dance like a Greek goddess.

Given the

above, it seems only reasonable I should find myself honing in on

Socrates. Mind you, I am no authority on the great ones of the ancient

past, other than being humbled by their wisdom and insight. Socrates is

for me the most interesting of the three: a perspective I am sure many

might agree and equally as many might disagree.

There are two statements that Socrates made that I found particularly thought-provoking.

“To know, is to know that you know nothing. That is the meaning of true knowledge.”

“Let him that would move the world first move himself.”

The first quote that starts, “To know, is to know that you know nothing”

is a paradox right off the bat. Yet, instinctively, somehow, I

understand the entire point and it makes sense even while being a total

paradox! And the second quote struck me as so linked and interrelated to

the first one. One would be hard pressed to assert one carries more weight than the other or to even think about them separately.

weight than the other or to even think about them separately.

weight than the other or to even think about them separately.

weight than the other or to even think about them separately.

How can we

know what we don’t know? Does the Socratic method offer us a technique

to advance towards the light of true knowledge?

Plato’s Dialogue: It’s About the Questioning

Socrates said: “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.”

In other words, question everything. I recently read the statistic that

children through the ages 2-5 ask roughly 40,000 questions. I have

wondered why, as we go through into adulthood, the number of questions

we ask drops significantly.

We know

through the writings of Plato, the student of Socrates, that he was

often quizzed by his teacher about deeper realities.  In “Plato’s Dialogues,”

we can read short works in which Plato recreates various conversations

Socrates had with another student. And thus, we get a really good idea

of the Socratic method.

In “Plato’s Dialogues,”

we can read short works in which Plato recreates various conversations

Socrates had with another student. And thus, we get a really good idea

of the Socratic method.

In “Plato’s Dialogues,”

we can read short works in which Plato recreates various conversations

Socrates had with another student. And thus, we get a really good idea

of the Socratic method.

In “Plato’s Dialogues,”

we can read short works in which Plato recreates various conversations

Socrates had with another student. And thus, we get a really good idea

of the Socratic method.

The style of a Platonic dialogue may go something like this:

Q: “What color is the rose in the garden?”

A: “The rose in the garden is red.”

Q:”Is this rose still red to a blind person?”

A: No.

Q: “So you are saying the rose is red only to those who can see.”

A: Yes.

Q: “What color would it be to a blind person? Would it be pink or white or some other color?”

A: (No answer – student is bewildered).

Q: “So the rose is red only to those who can see.”

A: Yes.

Q: “If the rose in the garden is where no one can see it, is it still red?”

A: (No answer – further bewilderment).

And so on.

The questioner might end up forcing a realization in the student of how

color only exists in a person’s mind as a result of their perception; it

isn’t actually a property of the rose. In other words, the rose is not

red.

Socrates

believed there were two ways to come to knowledge: through discovery and

by being taught. To be taught presupposes that someone else has

discovered the truth for you. He thought for his disciples to really know a subject, they should form their own beliefs and experience their own blind alleys and realizations.

How does this idea of discovery relate to the path of a Freemason?

From Darkness to Light

Every

Freemason is on a quest to discover his “true self.” He is taught the

importance of the Liberal Arts and Sciences, of which logic is one of

them. The study of critical thinking and reasoning allows the Freemason

to look beyond mere perception and dogma in the search for truth. In

this way, it is possible to forge a path to moral, scientific, and

philosophical enlightenment. “To know nothing” is leaning into

the next moment, wondering what you are going to find. It is a form of

being blindfolded or hoodwinked, waiting for more light.

It was in

Freemasonry that I really learned to embrace the journey from darkness

to light, to become a friend of the Socratic method, and learn to be

humble in what I don’t know. When I first joined, a poor blind

candidate, I was asked probing questions about the First Degree.

Questions like, “What does it mean to know thyself?” and “Is truth

absolute or relative?” I was asked to explore the relationships among

concepts and ideas. For example, I had to compare two types of symbols

and to explain how they are similar, how they are different, or evaluate

the meanings of each.

Over the

many masonic degrees, my mentors have pointed me in the direction of

truth only to glorify the beauty of the group vision and the image of

enlightenment.

The Freemason W.L. Wilmshurst said:

“Truth, whether as expressed in Masonry or otherwise, is at all times an open secret, but is as a pillar of light to those able to receive and profit by it, and to all others but one of darkness and unintelligibility.”

I think he is saying that truth is a mysterious something that is sensed, even though the  rational

mind may try to discredit it. The ability to sense this invitation to

truth, even when the path is dark and hidden, is perhaps the most

important lesson to consider here. “The future I do not see. One step enough for me.”

rational

mind may try to discredit it. The ability to sense this invitation to

truth, even when the path is dark and hidden, is perhaps the most

important lesson to consider here. “The future I do not see. One step enough for me.”

rational

mind may try to discredit it. The ability to sense this invitation to

truth, even when the path is dark and hidden, is perhaps the most

important lesson to consider here. “The future I do not see. One step enough for me.”

rational

mind may try to discredit it. The ability to sense this invitation to

truth, even when the path is dark and hidden, is perhaps the most

important lesson to consider here. “The future I do not see. One step enough for me.”

My takeaway from the Socratic method is this: Remember how little you know, question everything, and keep your mind open to other possibilities. If all goes well, truth is our travel companion from darkness to light. What do you ask for?

Service: Who Do We Expect To Change The World?

“Only a life lived for others is a life worthwhile.” ~ Albert Einstein

How many of

us have marveled at the courage and self-sacrifice made by a soldier

saving comrades in battle or a rescue worker who has saved families from

the peril of fire, flood and earthquakes. These brave souls run in to

danger when all others run away from it. What is that special code of

service that these rescuers live by?

I realize

that firefighters, police and soldiers receive special training to face

these perils, but there must also be a strong inner calling to serve

humanity within these devoted men and women, or they would have chosen other occupations. We have also heard stories of heroic behavior by ordinary citizens during catastrophes.

men and women, or they would have chosen other occupations. We have also heard stories of heroic behavior by ordinary citizens during catastrophes.

men and women, or they would have chosen other occupations. We have also heard stories of heroic behavior by ordinary citizens during catastrophes.

men and women, or they would have chosen other occupations. We have also heard stories of heroic behavior by ordinary citizens during catastrophes.

I recall

after the earthquake in California on October 17, 1989 how the community

I lived in became so cooperative and courteous with one another,

looking out for each other’s welfare. “Life as usual” ended and many

citizens were shocked out of their normal complacency. Instead, they

moved to help others in greater danger, without thought of self.

Although life does not ask most of us to save lives from physical peril, we are all given opportunities every day

to make a difference in the world. I constantly hear complaints about

how the world is going in the wrong direction, politics is corrupt, food

is poisoned, climate  change is the fault of humanity, immigrants are being treated unfairly, etc.

change is the fault of humanity, immigrants are being treated unfairly, etc.

change is the fault of humanity, immigrants are being treated unfairly, etc.

change is the fault of humanity, immigrants are being treated unfairly, etc.

Who is it that we expect will change the world?

We may not be able to change political corruption in an instant, but with patience and grooming future leaders, we could individually support new leaders who value the ideals that we hold dear. We could even groom ourselves as leaders for governmental office!

We may not

be able to fight against the greed of corporations on our own, but we

can support local organic farmers or grow our own gardens. We may not be

able to combat all of climate change, but we can reduce our own carbon

footprint and encourage others in our community to do the same.

Being an example to

others seems to be the best way to teach. We can be a light of

inspiration for those needing motivation and the light of tolerance for

those feeling judged; we can offer our

arms to hold another when they need comfort and solace; we can donate

money, clothing, food, or employment to those in distress.

our

arms to hold another when they need comfort and solace; we can donate

money, clothing, food, or employment to those in distress.

our

arms to hold another when they need comfort and solace; we can donate

money, clothing, food, or employment to those in distress.

our

arms to hold another when they need comfort and solace; we can donate

money, clothing, food, or employment to those in distress.

We can provide encouragement – to our brother who has fallen – that today is a new day. He or she can do better and even greater things starting right now; for whatever we sow today, we will reap tomorrow.

We may not be able to save the entire world. We can, however, start noticing what demands our attention during the day, and act when that still, small voice within says:

“It is your service that is urgently needed at this moment.”

Freemasonry: Is Architecture Frozen Music?

At the

end of a recent Scottish Rite workshop, and after one of the most

incredible weeks of my life, I felt inspired and nourished with the

treasures that only the craft of Freemasonry can offer. I jumped in the

car and set off on my long drive home. My thoughts were tuned to

philosophy, art, and music. I contemplated how a beautiful masonic

temple is a work of art, a finely tuned instrument, a Stradivarius

if you like. I had just been a part of something special; freemasonry,

philosophy and art teaming up together in my world for the love of

beauty.

So far so good.

But then the quote, supposedly of Goethe, crossed my mind, “Architecture is frozen music.”

Now, I like

Goethe very much. He was certainly a profound thinker, contrasting the

way architecture and music impact our minds. He gives you a sense of

what is greater than ourselves, what transcends our lives. I appreciate

the philosophical perspective. But, at the time I was thinking with my

snobbish musical mind that he got this one terribly wrong.

What about the reverse? If architecture is frozen music, does that mean music is liquid architecture?

You

certainly wouldn’t say that musical notes written on a piece of paper

is a complete definition of music. Of course not! A written melody is

perhaps one of the necessary components for a musical experience. But we

also need a musician who can read the notes and have the skill to

perform on an instrument. We need an occasion for this music to be

played. Don’t forget we need those listeners who can undergo the musical

experience. All these factors come together in a synergistic manner to

make up what we might call music.

You

certainly wouldn’t say that musical notes written on a piece of paper

is a complete definition of music. Of course not! A written melody is

perhaps one of the necessary components for a musical experience. But we

also need a musician who can read the notes and have the skill to

perform on an instrument. We need an occasion for this music to be

played. Don’t forget we need those listeners who can undergo the musical

experience. All these factors come together in a synergistic manner to

make up what we might call music.

Are you telling me that music is liquid architecture?

I don’t buy

it. Music is a complicated affair needing a host of ingredients working

merrily together to transport us into a state of musical rapture. Is

Goethe telling me that architecture requires all this movement to be

frozen still? How could Goethe be so wrong?

What Goethe really said

Well, as it

turns out Goethe’s analogy between architecture and music actually

extends much further. A little bit of research revealed to me that the

popular cliché has become distorted over time. “Frozen music” might

even be the most misleading definition of architecture around.

Goethe definitely said this in Conversations with Eckermann:

“I have found a paper of mine among some others, in which I call architecture ‘petrified music.’ Really there is something in this; the tone of mind produced by architecture approaches the effect of music.”

What I think

is the most important part of this statement is that Goethe was

suggesting that architecture produces the same “tone” or effect in your

mind as music. The point he is making is about the mind.

Let me

expand on my interpretation of his philosophy. If this is an act of

arrogance then I apologize, but for all my love of Goethe, my loyalty is

to truth and art.

Goethe’s

idea suggests something about the creative process of the mind and the

human need to express something. What would a building sound like if

the architect had been a composer? He would be using vibrations as the

medium of expression instead of lines and shapes. It could be said that

the musician “composes” using vibrations, the scientist “invents” with

formulas, the painter “paints” with color and design, and so on. A

thought-form is created. There is a universal theme of mental expression

underscoring all creative disciplines.

Goethe’s

idea suggests something about the creative process of the mind and the

human need to express something. What would a building sound like if

the architect had been a composer? He would be using vibrations as the

medium of expression instead of lines and shapes. It could be said that

the musician “composes” using vibrations, the scientist “invents” with

formulas, the painter “paints” with color and design, and so on. A

thought-form is created. There is a universal theme of mental expression

underscoring all creative disciplines.

It is the

special skill of the creative worker and the space in which they create

that causes a living architecture. These factors make the air molecules

vibrate in such a way that this soup of pulsating molecules works upon

our minds, even after the creative worker has completed his

architecture. We might call it a thought-form, a musical idea, that

continues to exist.

Freemasonry: The Creative Workshop

Freemasons

are always looking for connections between music, architecture,

geometry, proportion, and how such tools can be used to transform

society. Music doesn’t use windows or columns and architecture doesn’t

use melodies or notes. For most of us such obvious differences would

seem to eliminate any possible similarity between them. But wait! If we

use the idea that any artistic expression is a creative process of mind

then we get a very different picture.

St. Thomas Aquinas has said:

“Music is the exaltation of the mind derived from things eternal, bursting forth in sound.”

How

can a Freemason achieve that exaltation of the mind? I have a couple

thoughts on this. First, there is an acceptance of the possibility of a

more evolved world, and second there is an experience of a change in our

state of being as we become aware of that better world.

How

can a Freemason achieve that exaltation of the mind? I have a couple

thoughts on this. First, there is an acceptance of the possibility of a

more evolved world, and second there is an experience of a change in our

state of being as we become aware of that better world.

Temples and

buildings of great architecture are designed to build a bridge between

this world and that. There is something musical that pulsates and glows

inside them, inside the architecture, some dancing molecules that

converge as a product of all the thoughtful labor that has been

conducted until that point in time.

I should

point out that in a masonic temple there are no blurred boundaries

between participant and observer. Everyone has an active role in

building the edifice.

Architecture.

Music. And the relationship between them is….? I’m not sure, but the

obvious thing that springs into my mind is that the experience of a

beautiful building might in some ways equate with the experience of a

beautiful piece of music. The architecture inside the Lodge inspires the

Freemason outside the lodge to become a better Master Craftsman in the

mighty workshop of the Lord.

“Each Mason must be a builder; he is a workman under the direction of a Great Architect, who is planning a marvelous edifice, which is the Grand Lodge above, the perfect universe. To the building of this perfect edifice, each Mason must bring his stone, his perfect ashlar, perfect because it has been tested and proved true by the plumb, by the level and by the square.”~ Brother C. Jinarajadasa, Ideals of Freemasonry

Censing in Freemasonry: Practical or Symbolic?

The

act of censing has been said to create a pleasing and purified ritual

space. There is nothing quite as inspiring as walking in to a sacred

place and being hit by the smell of lovely incense, which immediately

transports us into a more reverent state of mind. What are the reasons

censing is important, or is it?

The Rite of Censing

came before, most, if not all, the current concepts of religion. It is

said to have originated from a distant past when men worshiped the sun

and other fiery forces of nature. Most researchers agree that there is a

connecting link between the use of incense in the ancient mysteries of

the past, and the speculative Freemasonry of the present day, for those

lodges who use incense. From what I have read, this connection can be

fairly well traced by archaeologists. However, there is less agreement

on why it is important.

Is censing and the use of incense in ritual more practical or symbolic today?

I recently read an interesting book called “A history of the use of incense in divine worship”

(1909) by Cuthbert Atchley. It contains a rather unique and objective

history of censing within ritual, both pre-Christian and Christian. I

especially enjoyed the section explaining various Egyptian ceremonials.

However, I was somewhat disappointed when I finally arrived at the end

of the book to hear researcher Atchley’s conclusions:

“The ultimate basis of all use of incense in the Church is its pleasant odour; that is, it is fumigatory. The more superficial reasons are what are called ceremonial.”

In other

words, he is saying that the main use of censing and incense is for

“deodorant” purposes, to mask awful smells and the stink of decaying

bodies, and so on. He says that any connection to ceremonial purposes is

“superficial.” While I might be somewhat forgiving because the book was

written over a century ago, the thinking underlying still seems flawed,

in my mind at least.

If something

did have a practical origin at some point in time, does that mean that

any symbolic value is of no account? Following from that, should it be

done away with accordingly?

It seems to me that this fails to think deeply enough about the nature

and function of ritual and ceremony – no matter what century we are

talking about.

accordingly?

It seems to me that this fails to think deeply enough about the nature

and function of ritual and ceremony – no matter what century we are

talking about.

accordingly?

It seems to me that this fails to think deeply enough about the nature

and function of ritual and ceremony – no matter what century we are

talking about.

accordingly?

It seems to me that this fails to think deeply enough about the nature

and function of ritual and ceremony – no matter what century we are

talking about.

Practical Origins

It is true

that many of the early uses of incense were practical and operative. For

example, the fragrance obscured odors, and was aesthetically pleasing.

There existed a mystical healing art hidden surrounding the use of

certain incenses. Ancient Egyptians (3000 BC) practiced medicine with

aromatic plants and even went so far as to establish astrological

relationships for them. There are many pictures that can be seen where a

Pharaoh is depicted with a censer casting the incense. Each

civilization, throughout the ages have all added their own contribution

to this handed down practical knowledge.

Over time,

the burning of incense formed a link to spirituality in a speculative

sense when it was offered to the gods alongside sacrifices and prayer.

Incense is mentioned frequently in the Hebrew Scriptures.

The psalmist expresses the symbolism of incense and prayer:

“Let my prayer rise like incense before you; the lifting up of my hands as the evening sacrifice.” (Psalm 141:1)

What the

ancients knew intuitively, science has verified today. Of all of the

five senses, the sense of smell is most strongly connected to the areas

of the brain that process memory. Even the smallest hint of a fragrance

that you had previously associated with a certain place can bring you

back to there in moments. Incense, then, is a way to tap the mind

quickly and with a great deal of exactitude. Certain combinations of

aromas can quickly adjust not only the atmosphere of the room but the

atmosphere of the emotions  and mind. Knowing all this, how, then, is censing significant in Freemasonry?

and mind. Knowing all this, how, then, is censing significant in Freemasonry?

and mind. Knowing all this, how, then, is censing significant in Freemasonry?

and mind. Knowing all this, how, then, is censing significant in Freemasonry?

A Symbolic Perspective from C.W. Leadbeater

Freemason Charles W. Leadbeater placed a great deal of importance on the ceremonial value of censing in his book “The Hidden Life in Freemasonry.”

He said that the entire process of censing in a Masonic Lodge is meant

to prepare and purify. It provides an atmosphere of solemnity and due

introspection. He explains that the ceremony of censing, being a

vortical movement, is connected with the way in which the Great

Architect has constructed the universe.

Leadbeater writes:

“In the movements made and in the plan of the Lodge were enshrined some of the great principles on which that universe had been built.”

He thought the censing ritual to be significant giving four main reasons:

- Raises the vibration of the lodge.

- Unifies the lodge members in thought.

- Bridges the inner worlds with the outer.

- Lifts and aids the candidate.

Leadbeater’s

premise is that the basis of any ritual is intent. The intentional

thoughts of the members set the purpose and vision for the ritual. The

lodge work concerns lifting and raising humanity from the human to the

spiritual kingdom. The Craft performed is therefore applied to the

mastery of the forces of one’s own nature, whereby “that which is below”

may become truly and accurately aligned with “that which is above.”

He says:

“The time has come when men are beginning to see that life is full of invisible influences, whose value can be recognized by sensitive people. The effect of incense is an instance of this class of phenomena… each of which vibrates at its own rate and has its own value.”

Any of us

who has experienced censing may have a different opinion of what it

means. Practical or symbolic? Perhaps both? For myself, censing kindles

a wonderment at the eternal mystery of an all-knowing Deity, whom we

have not seen and cannot yet see clearly. Our human vision is not suited

to that. The smoke obscures the air briefly. It is salutary for us to

be reminded every now and again that our concept of the Most High is

always incomplete, inadequate; that he is other, transcendent, and holy.

The Masonic Pursuit of Freedom

What makes a Freemason free?

I started brooding over this question one day when wondering which word